“This Old House”

Dwayne Grant – Gold Coast Bulletin – Paradise Magazine February 7th, 2009

FOR a moment, just one mystical moment, we want you to believe in ghosts. Let go of your doubts, throw away your cynicism and imagine a world where our forefathers float through the streets of our city trying to comprehend the way their humble township has evolved since they last drew breath.

In particular, we want you to believe in the ghost of Tom Lather and join him as he drifts along Southport’s Nerang Street towards the Broadwater. A fit and healthy Tom roamed these parts more than a century ago, the sixth eldest of 11 children to German migrants who had settled at Southport — or Nerang Heads as it was then known — in 1875.

In particular, we want you to believe in the ghost of Tom Lather and join him as he drifts along Southport’s Nerang Street towards the Broadwater. A fit and healthy Tom roamed these parts more than a century ago, the sixth eldest of 11 children to German migrants who had settled at Southport — or Nerang Heads as it was then known — in 1875.

After enduring a five-day trek from Brisbane to start a new life in a new community, the Lathers became synonymous with the fledgling township. Only 30 people called Southport home in those tough pioneering days and Tom’s family was one of its most prominent, so much so the local cricket team of 1883 included only one player who didn’t have Lather blood flowing through his veins. But that was then.

Nowadays Tom’s ghost finds himself in a Southport vastly different to the one he left behind when he died in a football accident in 1895. This Southport is filled with concrete buildings where Tom’s cows used to graze and sleek cars speed along bitumen roads that were once bush tracks designed for horse-drawn buggies.

The ghost of Tom is now a stranger in his own land and as he climbs a rise in Nerang Street, he finds himself passing yet another apartment block under construction, a building that would’ve dominated the landscape back in his day but barely warrants a second glance from today’s passing motorists.

When he arrives at the top of a hill he once knew so well, the ghost of the one-time dairy farmer is confused by the scene that greets him to the east. Instead of seeing sunlight bouncing off the Broadwater in the distance, he finds himself staring at more and more roads, more and more buildings and a multi-storey monolith called the Gold Coast Hospital.

Panic-stricken, Tom’s ghost searches for something, anything that will tell him this is the place he once called home but nothing registers. The shape of the land might be familiar but nothing that rests upon it is.

But what’s that?

From the corner of his eye, Tom’s ghost spies something that quickens his lifeless pulse. For the people roaring past in their mechanical beasts it is just another roofline but Tom has seen that roofline before.

From the corner of his eye, Tom’s ghost spies something that quickens his lifeless pulse. For the people roaring past in their mechanical beasts it is just another roofline but Tom has seen that roofline before.

He floats towards the lacework fence surrounding the property on the corner of Nerang and Pohlman streets and drifts through it to uncover a sight that takes him back across the decades.

In a world where absolutely nothing has stayed the same, the ghost of Tom Lather has found a building that still stands 123 years after he first hammered nails into its framework, 123 years after he first fed poddy calves within its grounds, 123 years after he first curled up beside his beloved Alice Matilda within its walls.

After more than 120 years, the house that Tom built is still here.

Surrey House still stands.

Dr John Corbett is a pleasant host, a softly spoken man who takes obvious pride in the property he calls home, yet one can’t help but sense he isn’t entirely comfortable showing off his exquisite old Queenslander to strangers’ eyes.

Behind the friendly smile and warm handshake, it’s almost as if you can see him debating whether he’s made the right choice in granting a journalist and photographer access to his private sanctuary so they can splash it over these pages.

Unlike some property owners who love the acclaim that comes with owning a prominent home, John and wife Lorraine have never courted publicity about Southport’s Surrey House and the painstaking years they spent returning the 19th century home to its former glory.

They have now changed their minds, however, and the reason for that can be summed up in one word — history.

“We’ve never gone out to make a point about the house but we think it’s important for the community to know what it offers,” says John, a neurologist and sleep physician whose clinic operates from the property’s ground floor. “There are comments from time to time that the great thing about Gold Coast heritage is there is none. Well, we don’t think that’s true.

“There are not a lot (of heritage buildings) but that’s what makes a place like this more important. What we have should be treasured … and that’s the reason we’ve decided to break the habit (of not promoting it).”

John and Lorraine’s decision to open their doors can also be traced to a little-known fact they unearthed in recent years when they investigated the history of their home. While they knew Surrey House had stood on its elevated site since the late 1800s, little did they — or anyone else — realise they were residing in what is believed to be the oldest surviving residence in Southport … and possibly the Gold Coast.

“It was almost like stumbling on a lost tribe in Africa, a direct link to our past,” he says. “A lot of people know of the house because it is heavily trafficked and prominent but not many people know just how significant it is in terms of its age.”

The Corbett’s commissioned architect and heritage conservation expert Arnold Wolthers to independently confirm their findings and his resulting 100-page report is not only the story of a house but also of the people that laid the foundation for the Gold Coast. The hardships and obstacles the early settlers endured in establishing a community where no roads previously led are a world away from this modern one where office workers threaten to riot if the air-conditioning breaks down.

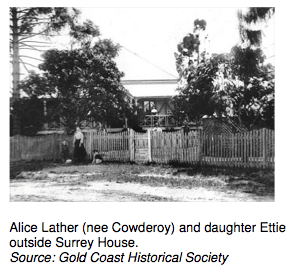

Those early settlers were tough men and women and foremost among them were the Lathers and the Cowderoys, two migrant families who sired 20 children between them well before baby bonuses made conception an immaculate idea for some. Bonded in the mid-1880s by the weddings of two Cowderoy girls to two Lather boys (John and Louisa; Alice and Tom), the families were soon riding the fortunes of what was being promoted to Brisbane’s landlocked masses as a resort town.

Having already acquired four property lots in Southport as a spinster, Alice soon had another real estate interest in 1885, the same year the Gold Coast Bulletin began its life as the South Queensland Bulletin, when her husband-to-be purchased the two lots upon which Surrey House would be built.

The prominent high location — and the house they built upon it — would soon become an entrance point to the town when the new Southport to Nerang Road was forged, marking the first glimpse of the ocean and the township of Southport below.

It has been suggested Tom built Surrey House with the assistance of older brother John as both of them had worked in the building trade, the latter having built many of the district’s homes. Their father, John Lather Sr, had purchased the Southport sawmill on the banks of the Nerang River several years earlier and in all likelihood the timber they used was the product of the old man’s enterprise.

This was the era of the cedar getters, those hard folk of northern NSW who would fell giant trees and use creeks and streams to float their logs down the Richmond and Tweed rivers.

Often was the time they simply tied their logs together and rode them across the Ballina or Tweed bars on the outgoing tide before waiting for the northern stream to carry them towards the Broadwater to the north.

While some were swallowed by the sea and others arrived on dry land stark raving mad after being forced to drink saltwater while drifting at sea, those who successfully crossed the Southport bar on the incoming tide would celebrate with a hearty drinking session at the Pacific Hotel.

Originally a four-roomed homestead with an encircling veranda, Surrey House, like many Southport properties of the time, was built on stumps in the classic Queenslander tradition, with many a housewife grateful for the covered space underneath to dry clothes on rainy days. Inspired by the tents of the British Raj, the design also featured a wide open breezeway through the centre of the house to provide increased ventilation, as well as high ceilings to ensure hot air had somewhere to rise.

Another key feature of Surrey House still visible is the exposed framing. While Victorian architectural custom promoted cladding the walls on the outside as a statement of wealth, the Lathers departed from the script.

One theory for their decision is some early builders had previously been shipwrights and were familiar with a similar concept of building wooden boats in a light but strong and economical fashion. As a rule, only those external walls not directly exposed to weather displayed the feature, notably those protected by verandas.

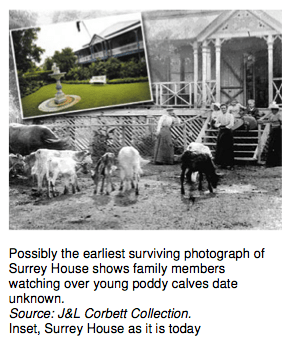

As well as living in the house, Tom and Alice Lather ran the Surrey House dairy on Nerang Road for Alice’s father, John Cowderoy, supplying much of the local area with butter and milk. An undated photo of family members sitting on the front steps of Surrey House has survived to this day and shows a milking cow and young poddy calves being fed.

An assortment of Lathers and Cowderoys called Surrey House home over the years until the family moved to a new property in Scarborough Street in 1911. With the surrounding farming land carved up, the house had many owners during the first half of the 20th century and suffered some neglect until Dr Paul Larkin, a distant relative of John Cowderoy, purchased the ‘dilapidated’ property in 1968.

“We had to put a hose through the place,” the doctor told the Gold Coast Bulletin a decade later. “A shed in the back yard was full of old farm implements. We also found a cow dip near the fence line so turned it into a rose garden.”

It is believed Surrey House was raised off the ground after Dr Larkin’s arrival but what is certain is the manner in which the doctor nursed the property back to health.

A back extension was added, along with two cottages to the side and rear of the house. He also added rooms underneath to accommodate a surgery for himself and two other doctors.

Photos from the period show a spectacular home, lovingly preserved and renovated by the Larkin family, and when the time came to sell it after 26 years, there’s every chance they hoped for a buyer who would keep the legacy alive.

In John and Lorraine Corbett, they found just the right couple.

The irony of the unique place the Corbett’s now have in local heritage circles is they originally didn’t want to live on the Gold Coast when they returned from several years living overseas.

“I thought we’d go back to Sydney and this house is why we stayed here,” says John. “We saw the house and thought ‘what a fabulous place’ … people tended to say ‘you wouldn’t want an old Queenslander’ but we thought the reverse. We thought it was just fabulous.”

As a neurologist of some renown, John has an impressive resume — a Rhodes scholar, Oxford and Harvard alumnus, a stint at the world-renowned John Hopkins Center. Listen to him talk about his home, however, and it’s clear he’s just as proud of the work he and his wife have done on Surrey House than any of his professional achievements.

Following their purchase of the property in 1994, a labour of love began and they threw their energy into creating a home that blends the grandeur of yesteryear with the functionality of modern-day life. Enormous effort has gone in to ensuring every original floorboard, wall and railing has been restored to perfection, while any extensions to the home were carried out only if they complemented the timeless tone of the property.

“If you want something to be preserved for posterity, you have to make it functional and usable,” John explains of their decision not to pursue heritage-listing. “If you simply say it’s a museum item, it goes unused. It’s not maintained.”

The interior of the original home remains intact and boasts 3.6m (12ft) ceilings and french doors leading to the verandas, while the wall-lining timbers consist of 25cm- wide panels and were typical of the colonial era. The entrance door is also a sight to behold — an impressive red cedar door with a massive door-lock that exudes an air of status.

John’s guided tour is littered with references to the lengths the couple went to find the right materials for the restoration — wood panels from Rockhampton; 100-year-old timber from an old Fortitude Valley building; even a couple of original lamp globes from Brisbane’s iconic Grey Street Bridge to adorn the front gate.

A visit to the original living and dining areas is a visual overload thanks to an array of antique furniture, ornaments and paintings, not to mention three spectacular chandeliers that send your eyes skyward.

Being a proud father, John also points out the various paintings hanging within the home that were done by their only daughter, Vanessa, while evidence of grandchildren Harrison and Brooke can be witnessed in the toddler security gates atop the internal staircases. These aren’t plastic barriers from Kmart though, with even these timber creations specially carved to match the original cedar on the staircases.

And while the home is impressive, John can’t hide the affection from his tone when he talks about the gardens outside and, in particular, the tranquil setting just outside his clinic’s entrance.

It is here his patients retreat when it’s time to ponder the sometimes difficult news they’ve been delivered inside, all the time watched over by a magnificent old tree.

“You only get a 100-year-old tree by planting it a hundred years ago,” smiles John as he returns to his theme of preserving history. “You can’t just put another twig in and say ‘that’ll be right’.”

As the ghost of Tom Lather knows so well, progress waits for no man and the present- day owner of the house he built 123 years ago is well aware its iconic location may well create headaches in years to come. As he casts his eyes across the fence to one of the Gold Coast’s main thoroughfares, John acknowledges there could come a day when a battle has to be waged between the desire for wider roads and the need to preserve a historic home.

“I’m very comfortable about development but I just think there’s so precious little left that places like this need to be preserved,” he says. “We’re very conscious that Main Roads at one time wanted to resume (this area) and the house wouldn’t have been here. They would have come right through here and they didn’t even know it was an old house.”

Heritage advocates shouldn’t fret though as one gets the impression that as long as the Corbett’s own Surrey House, the legacy of our forefathers is in very safe hands indeed.

“We feel passionately we’re the custodians of the place and we’ve got a responsibility to preserve it,” says John.

“It’s no good saying ‘they ought to do it’. We’re the people in the seat and if we don’t do it, it won’t be here.

“We’re just the passing owners. One of these days we won’t be here any more but the house should be maintained. We just want it to be here forever and there’s no reason to think it can’t be.”